DO ACID-FAST NUCLEI (STEM CELLS) EXTRUDED FROM ERYTHROBLASTS SUPPORT THE MITOTIC POTENTAL OF MALIGNANT TUMOURS?

Palacios-llopis SL General Goded nº 5 . # 7 Arrecife de Lanzarote. 35500 Las Palmas. Spain.Tª/Fax 928-806065 e-mail: sldpalacios@eresmas.net

Abstract

Adult stem cells arise from extruded near naked nuclei of immature erythroblasts. Enucleating erythroblasts support near naked nuclei to primary and metastatic human tumours. According to the axio-somatic model, neoplastic and embryonic growth is sustained not only by the mitotic potential of resident cells but also by the additional mitotic power supplied to these growths by near naked nuclei (stem cells) coming from erythroblasts. The concept of mitotic potential is closely associated with the presence of replicons in nuclear DNA, or autoreplicative highly repetitive DNA sequences, occurring in the non-protein coding portion of the genome. These naked nuclei can be typed in tissues by their extreme nuclear chromatin compaction and by their acid-fast waxy envelope (acid-fast lymphoid cells). Chromatin compaction and acid-fastness also occur in adult stem cells. The presence of mycolic acid in these waxy membranes need to be investigated opening a way for their specific immuno-phenotyping. Adult stem cell nuclei containing self-replicative DNA are highly unstable and thermolabile, and compaction may prevent their spontaneous nuclear segmentation. Acid-fast naked nuclei are uncommitted cells, and commitment is imparted by local cytoplasmic or extracellular instructions. If acid-fast naked nuclei are extruded in bone marrow, they may give rise to hemolymphatic precursors (hematogones). However if acid-fast nuclei, insulated by erythroid cytoplasms migrate to extramedullar tissues, on extrusion these virgin nuclei become committed stem cells for many tissue types, which may be targets of these nuclear grafts. The latter, linked to the concept of Karyoanabiosis, is obvious during early human organogenesis. More significant is that acid fast-stem cell disguised as erythroblasts and/or acid-fast stem cells probably also support the mitotic potential to neoplasias (oncotropic stem cells). Sperm and adult stem cells are thus essentially acid-fast vectors (centriole-DNA complexes) of mobile, self-replicative DNA to mutant targets, mediating transformation by fertilization. In the axio-somatic model, the on/off switches and the regulation of embryonic and neoplastic growth depend on supracellular events, including organ to organ (bone marrow-somatic tissues) and cell to cell interactions. Between bone marrow and tumours there is a blood stream phase, in which transforming erythroblasts can be tracked down. Transient erythroblastemia may be a feature of cancer patients. Accordingly new therapeutic approaches need to be developed. To test these hypotheses we propose a process of chronic selective hemofiltration and thermomodulation for retrieving and destroying these thermolabile acid-fast nuclei in patients with cancer, as well as clinically monitoring the process of tumour growth.

INTRODUCTION

Recent papers have highlighted the role played by bone marrow derived stem cells in neoplasia(1).Previous speculations have suggested that the growth of malignant tumours is likely sustained not only by the mitotic potential of the tumour cell population but also by the additional mitotic power supplied by the nuclei of exogenous erythroblasts which are periodically grafted into neoplasic tissues (2). Embryogenesis, regeneration and cancer are probably all forms of tissue proliferation, with each dependent on stem cells of hemopoietic origin . This hypothesis is rooted in the framework of the axio-somatic (AXS) model (2), which is based on current concepts of human reproduction considered a paradigm for cancer histogenesis. The basic objective of sex is the combination of two different types of DNA: an autoreplicative or axial (AX)-DNA, and a protein coding or somatic (S)-DNA. This interplay between two functionally different nucleoproteins has been observed in prokaryotes, i.e. during transformation by replicon insertion, as well as during the mitosis and fertilization of eukoaryotes. The testis is a generator of mitotic potential, from which it is exported as mobile centriole-DNA complexes in spermatozoa (2,3). Throughout fetal oogonial mitotic expansion, the ovaries generate a potential for neodifferentiation. Asynchronous oogonial phenotype senescence gives rise to mature ovocytes, mitotic senescent cells involved in genomic recombination and the transcription of differentiating DNA. The ovum is a mutant cell with a cytoplasmic microenvironment enriched with the raw proteins destined to guide the differentiation pathways of prospective transfected nuclei (4). During embryonic induction, the first level of decision making depends on supracellular events, including person-to-person, testis to ovary, and sperm to ovum interactions. By analogy with the former assumptions, the generation of malignant tumours in humans disposes with the cellular hierarchy and the on/off and maintenance switches of processes derived from supracellular vents, with emerging instructions not evident at the molecular or genetic levels. Cancer results from the interaction between two different clones of cells (bi-clonal model). The first clone is formed by axial stem cells of actual germ cell origin, which they are generators and vectors of mitotic potential. The second interacting clone, the target, is represented by mitotically exhausted somatic cells in distal phenotypes, which they are involved in genomic mutations and generate the potential for neodifferentiation. The potentialities of both axis and soma are transformed by fertilization in effectively growing mutant phenotypes. The genome of a somatic cell is a hybrid of both types of DNA, and, if mitotic expansion and differentiation are operative in depleting the genome of ax-DNA, fertilization is instrumental in the enrichment of the target genome with ax-DNA.

BONE MARROW (AXIS)–SOMA INTERACTION IN CANCER

The axis of the body and the axis of bones are sites of particular mechanic and quantum stresses (2,3).The axis of cells which are seated in the axis, are sites of crystallization of centrioles and related microtubules (5). The centriole-microtubular complex links specific segments of cell membranes to kinetochores, centering the absorption and distribution of quanta to key DNAs and transforming alu-repeats in high energy “hot” replicons. Furthermore, the pattern of symmetric/asymmetric cell division is centered on the axis. At this site, the centriole acts to handle AX-DNA during mitosis, separating replicon rich stem cells from replicon depleted differentiating cells. The sperm and germ line hematopoietic stem cells have in common a well developed centriolar DNA complex. In male gametes the tail, a centriole linked appendix, handles mobile, replicon rich DNA before fertilization and the male centriole masters karyogamy and the first mitotic divisions of the embryo(6). In stem cells we have observed the presence of a uropod (Fig. 1), which had been previously described in lymphocytes (7), as epitomized by the “hand mirror lymphocytes” of some leukemias. Gametopoiesis, hematopoiesis and thymic lymphopoiesis are central generative processes seated in the axis of the human body, and are hypothetical sources of mitotic potential. The nuclei of mobile stem cells are vehicles of mitotic potential. One example is AX-DNA, which is probably transported in the nuclei of sperm and erythroblasts in the form of “hot” compacted chromatin insulated in acid-fast (af) waxy membranes (8). It is essential to understand that the concept of mitotic potential is closely associated with selfness (9), which is present in replicons, or alu containing repetitive sequences in heterochromatic, non-protein coding DNA. Replication is linked to the structural presence of “replicons” in DNA and to their functional counterparts, “hot” replicons. Centromeres are replicon rich segments of waste DNA involved in mitosis. A low number of replicons in DNA is thus indicative of low mitotic power, whereas a replicon rich DNA is indicative of a high mitotic potential.

The soma is involved in unequal mitotic expansion and exhaustion (asynchronous phenotype and clonal senescence)(2,3) and develops distal foci of replicon depleted, mitotically exhausted cells. This situation triggers genomic recombinations and mutant atypical cells. These cells, which are low replicators, with open genomes creating neodifferentiation, are specific candidates for fertilization by exogenous DNA. Differentiation potential is present in local cytoplasmic and extracellular instructions. During nuclear transfer, mitotic potential is exported to a local microenvironment, facilitating the expression of the local phenotype (differentiation) through cellular mitotic expansion. This is evidenced during regeneration, where nuclear grafting has an enhancing proliferative effect on the target phenotype. There are no genotypic changes in the rejuvenated tissue and contact inhibition is operative. In neoplasia there is a significant change in the target side, where the concept of neodifferentiation emerges. There are genomic recombinations in the field, and a mutant phenotype would arise that lacks contact inhibition with the surrounding tissues. The transfert of selfness, throughout mobile replicons to the mutant tissue, is instrumental in malignant transformation. According to former assumptions of the AXS-model (2), the nuclei of some erythroblasts are AF-vectors of selfish DNA mediating transformation by replicon insertion.

THE MEANING OF FERTILIZATION

The finding of a high number of replicons per unit of DNA in blastomeres and a small number of replicons in post-meiotic gonias and in distal somatic cells (10) supplied a link between fertilization and the acquisition of active replicons by the ovum (3). The sperm is a fully developed waxy membrane centriole-DNA complex that transfers energy from the axis to the target DNA in the ovum. This is mediated by the transport of hot replicons. In karyogamic events, the mitotically arrested ovum loses the rest of its exhausted centriole-DNA complex through polar body extrusion, and this is replaced by the energizing centriole apparatus of the male gamete. The handling of DNAs by centriole derived structures is probably underpinned by resonance with the external field and signifies energization of the replicons. This is likely operative in the axial gonad and along the swimming pathway between testis and ovum. A comparable but artificially induced absorption of quanta by specific segments of DNA also takes place during in vitro manipulation and transport of somatic nuclei destined for grafting in enucleated ovums. Ignoring the transcendent role played by the quantum state and organization of differing external and internal fields is a source of basic misconceptions about in vivo versus in vitro systems*. In cloning with somatic nuclei, the relative numbers of replicons present in these artificially energized nuclei limit the mitotic self-renewal capacity of the exitous conceptus. The transfected nuclei coming from non-stem and distal somatic cells, with low numbers of replicons, can give rise to fully developed but smaller animals, which are prone to accelerated mitotic senescence (11).

*In vitro there are immortal clones, in vivo they are not.

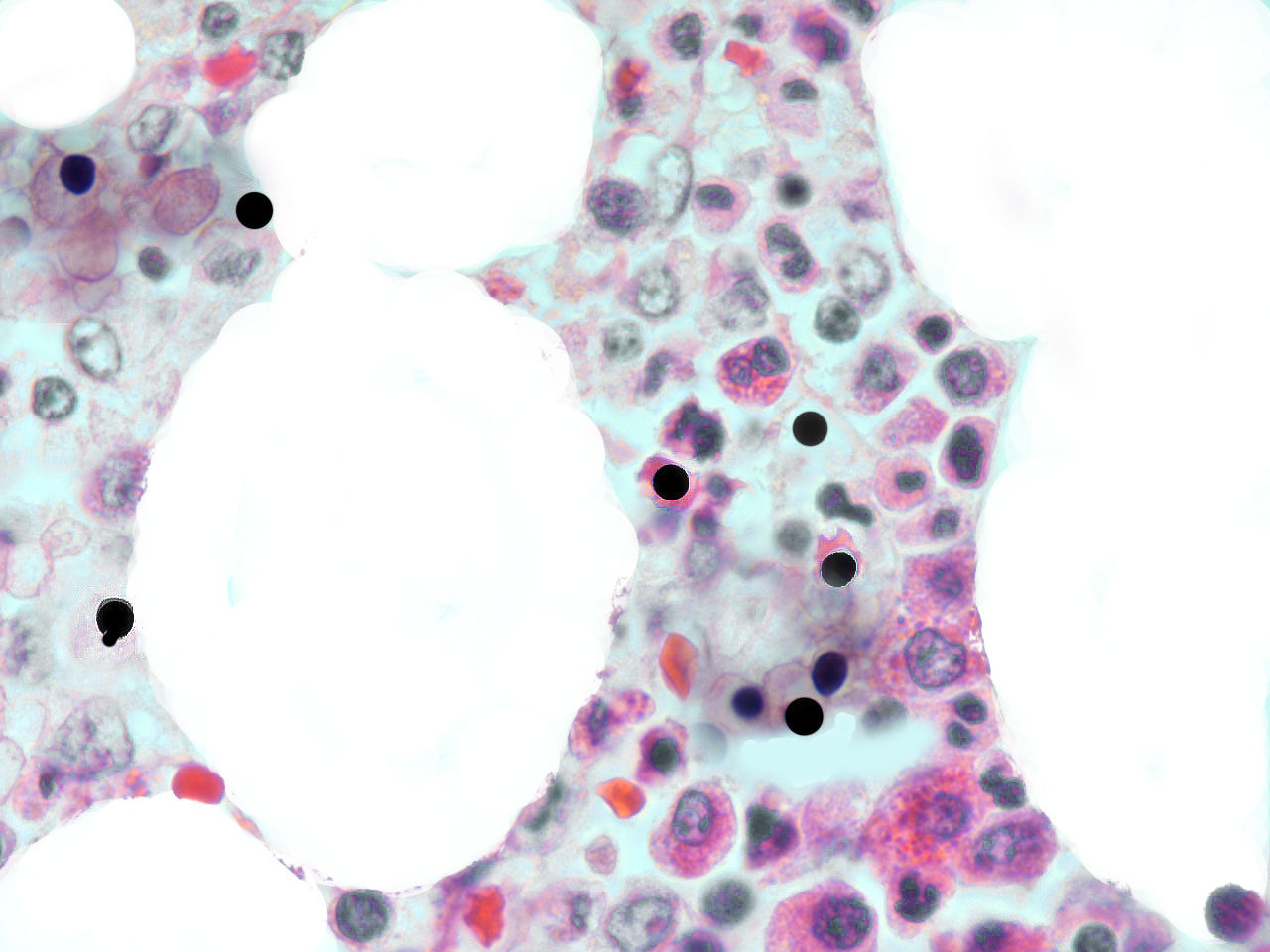

EVIDENCE FOR THE ERYTHROBLASTIC ORIGIN OF HEMATOGONES

We have previously presented evidence of the erythroblastic origin of hematogones (12). Hematogones are lymphocyte-like cells presenting as a near naked hyperchromatic nuclei (fig.1). In normal adults, 12% of erythroblast nuclei show a substantial degree of myelinization (13), which correlates with the acid-fastness of these nuclei, which on extrusion from the erythroid plastid, are enveloped in ceramide containing membranes, giving rise to acid-fast (AF) near naked nuclei (NANU). Hematogones are cells originating in other cells by a non-mitotic mechanism (extrusion) and can be typed in tissues as AF-lymphoid cells.*

* We use the term hematogone accordant with its etymology and ontogenic sense.

Extruded erythroid nuclei can give rise to all of the hemolymphatic lineages.

fig.1

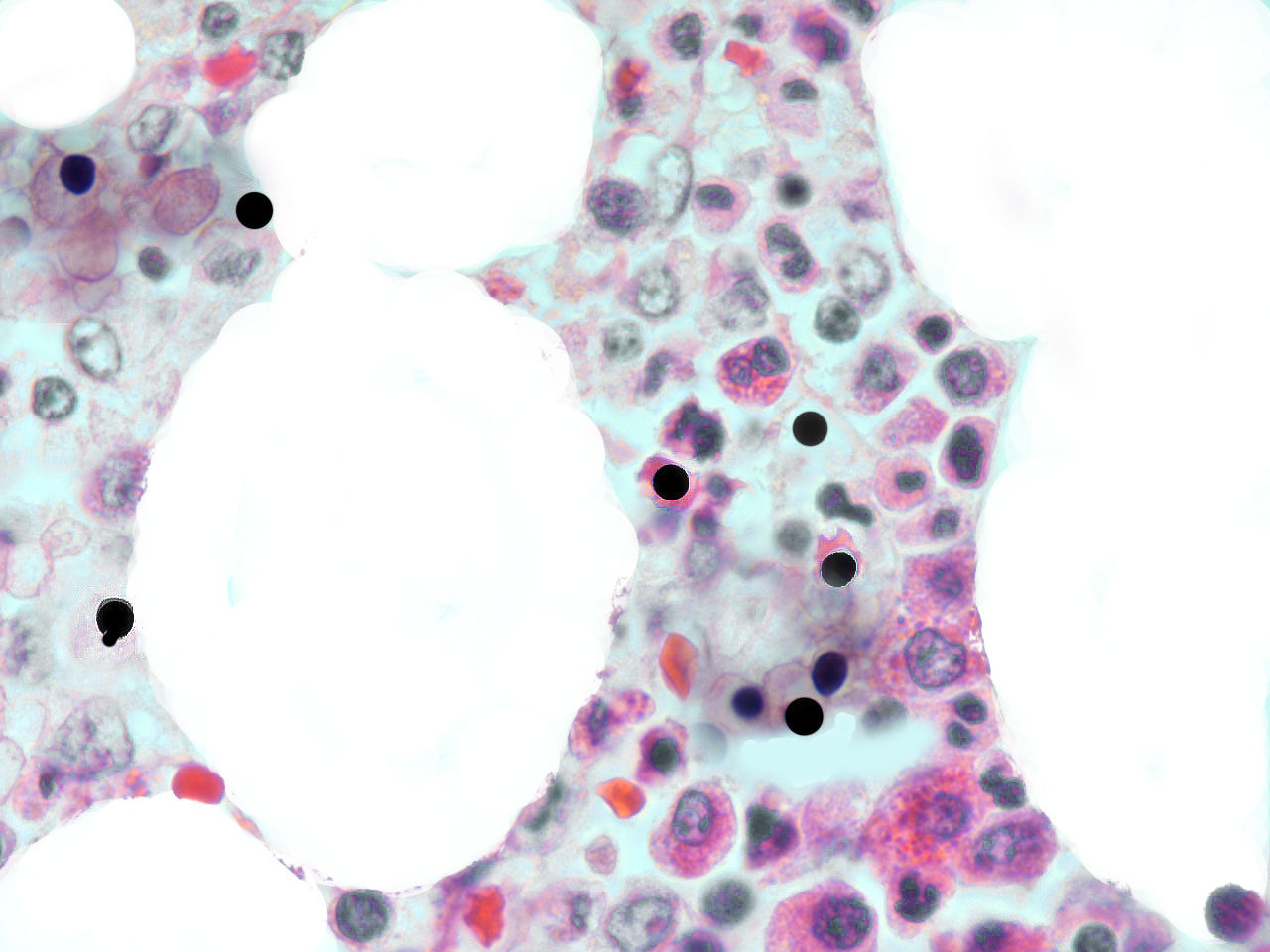

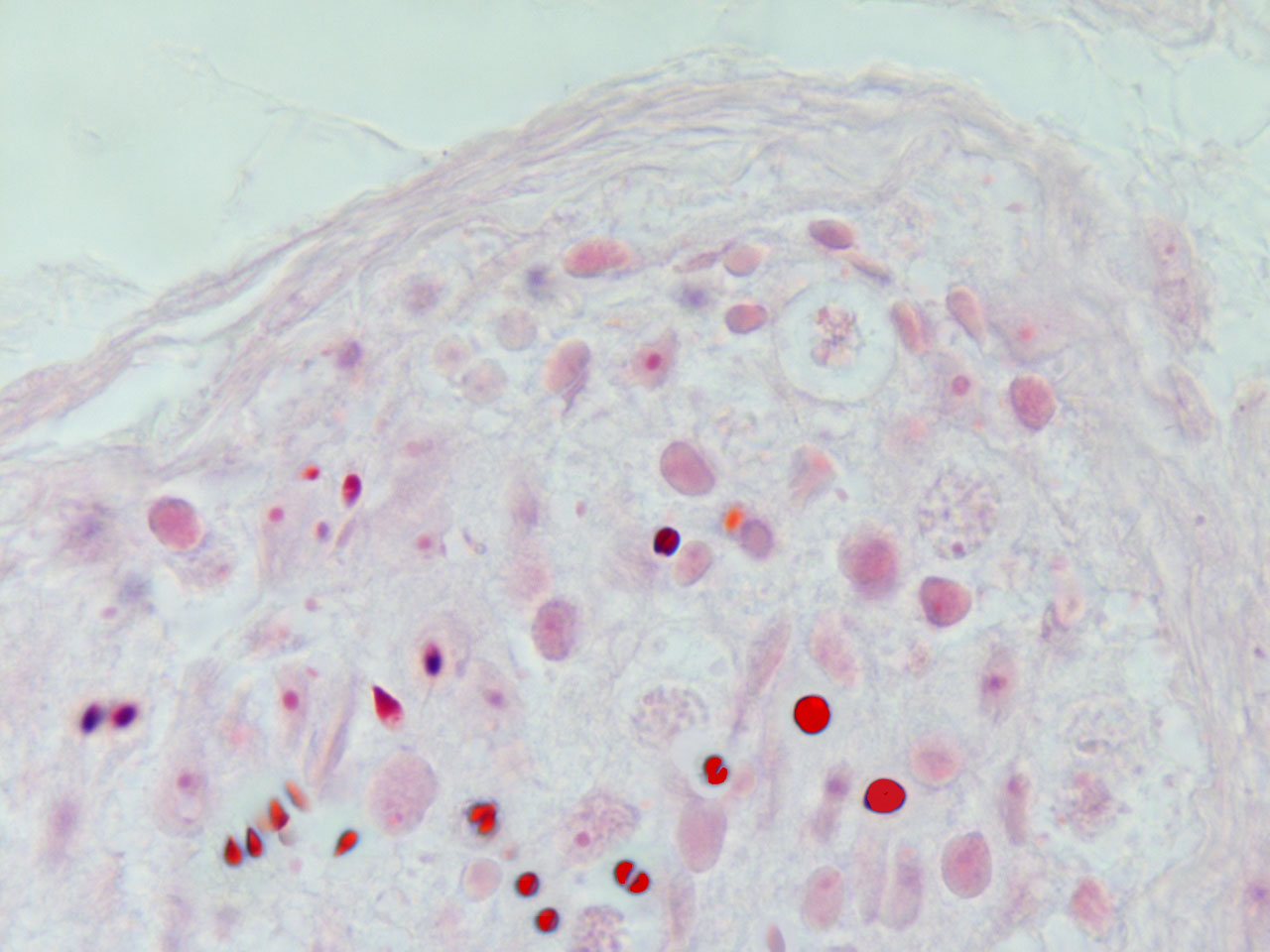

Hematogones were initially thought to be precursors only of B-lymphocytes (14), but there is evidence that they are endowed with a wider differentiating plasticity. In fact these hematopoietic stem cells can give rise to many non-hematopoietic epithelial tissues (15). AF-stem cells are exported to somatic tissues as primary erythroblasts and/or as AF-lymphoid cells; that is, nuclear extrusion can take place inside or outside of the medulla. Recently extruded AF-NANUS are probably very sensitive to tissue specific molecular instructions present in all possible local microenvironments. The erythroid cytoplasm and the waxy nuclear membrane prevents these travelling virgin nuclei from the differentiating pressure of changing tissue scenarios. Erythroblastic nuclear extrusion taking place in bone marrow gives rise to a local “hemolymphatic” phenotype, whereas, if nuclear extrusion occurs inside the bloodstream or in peripheral somatic tissues, the local microenvironment directs differentiation to its own histologic type. In embryo-fetal tissues, there is a high incidence of erythroblasts and of af-nuclear extrusion over rapidly growing sectors. (fig.2)

fig.2

This transfer of exogenous nuclei to tissues has been called “nuclear grafting”(15), and the incorporation of these nuclei into local populations takes several forms:

1) Karyoanabiosis, in which intact nuclei are grafted into the target and subjected to immediate local commitment, i.e., restricted differentiation and replication. 2) Amitotic nuclear segmentation or reduction division, an apoptosis like mechanism that gives rise to haploid and less than haploid centriolar-nuclear complexes, which will be involved in karyogamic events within local populations. These observations suggest that embryo-fetal growth is sustained not only by the replicative power of local populations but also by the nuclear mitotic potential present in recently incorporated stem cells of erythroblastic origin. A similar mechanism probably operates during regeneration. In adult tissues erythroblasts and nuclear extrusion of af-cells outside the bone marrow is present at a very low range, paralleling the low regenerative power observed in humans.

EVIDENCE OF PRIMARY ERYTHROBLASTS ENUCLEATING WITHIN

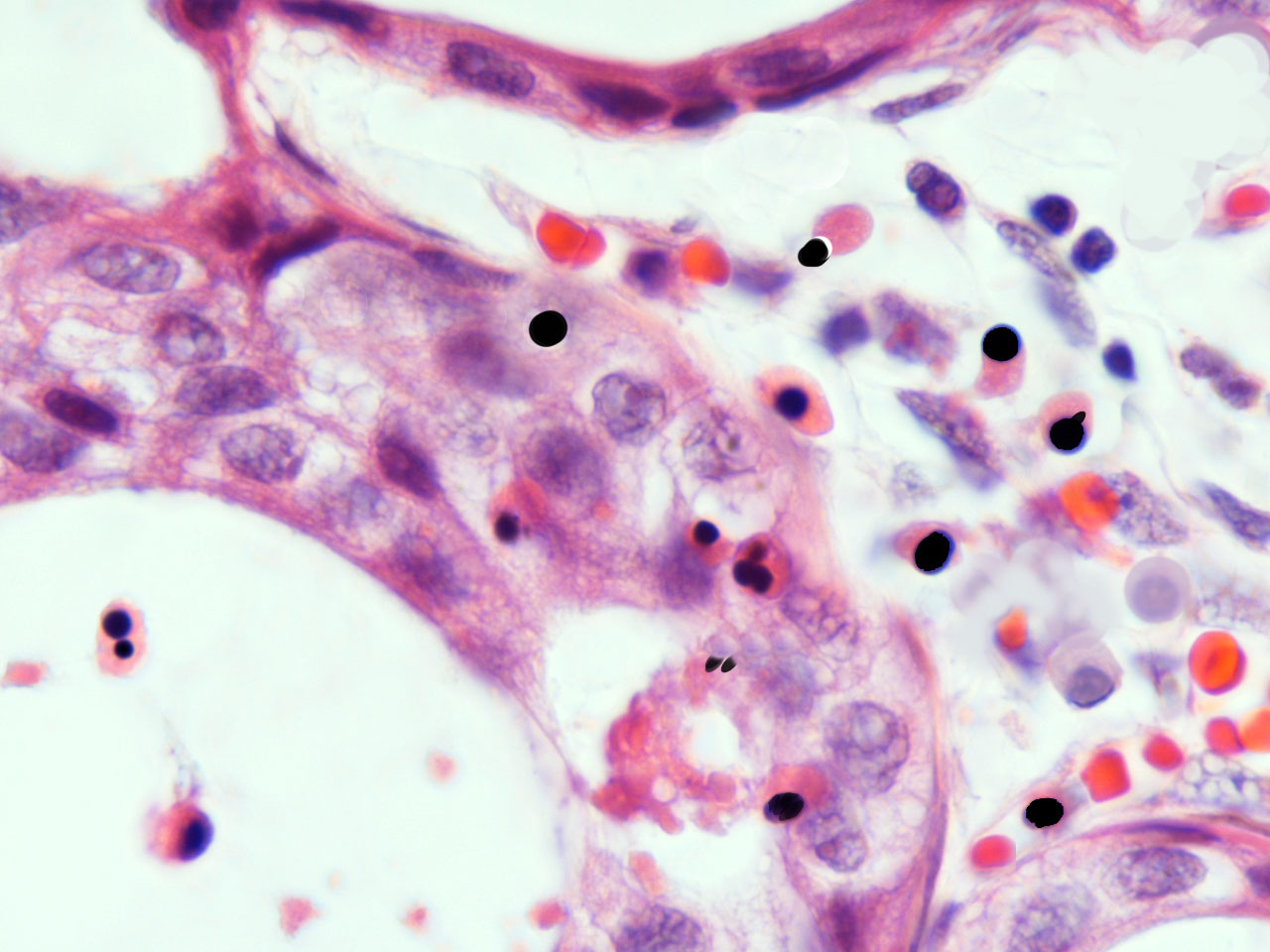

NEOPLASTIC TISSUES

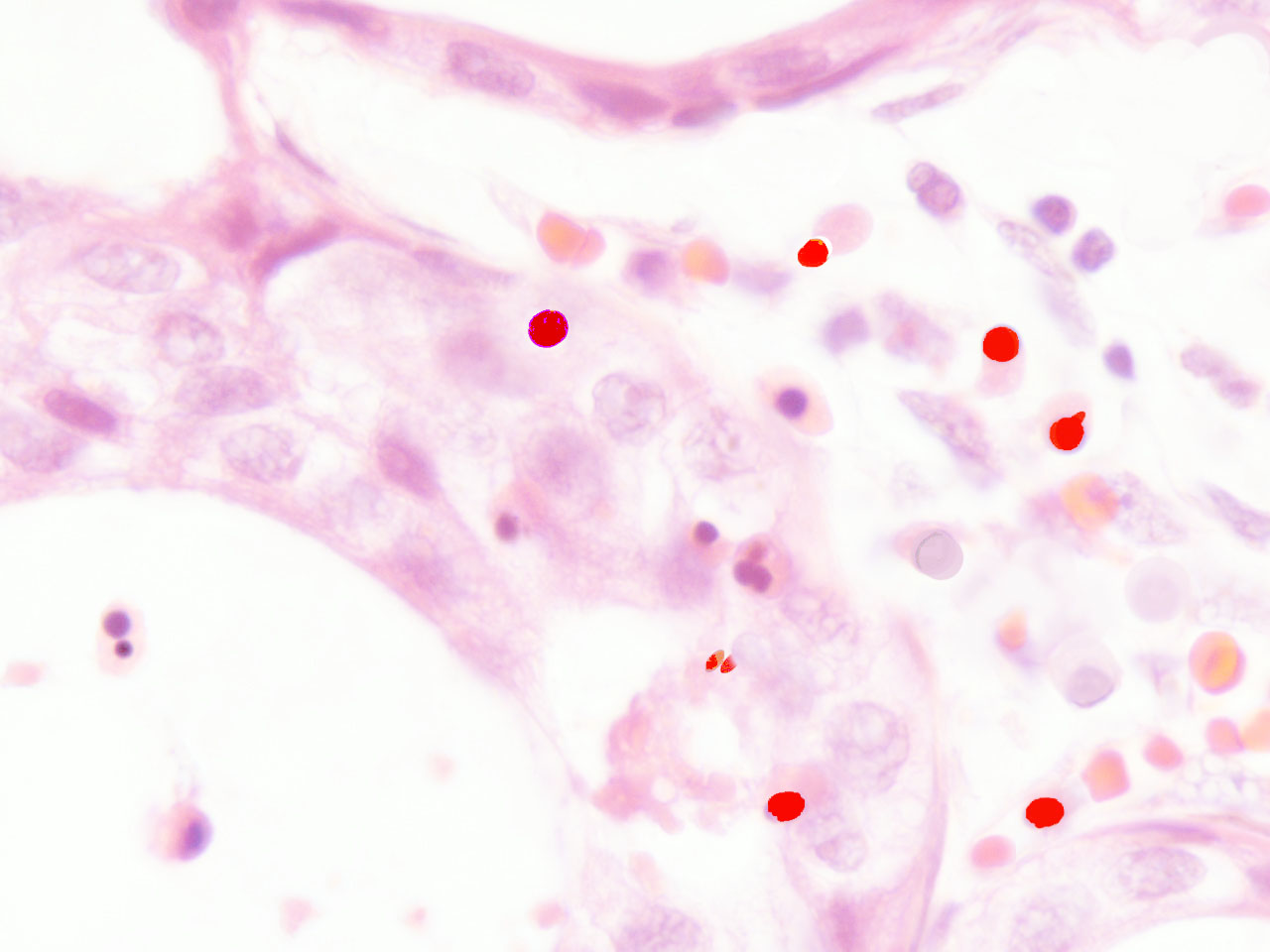

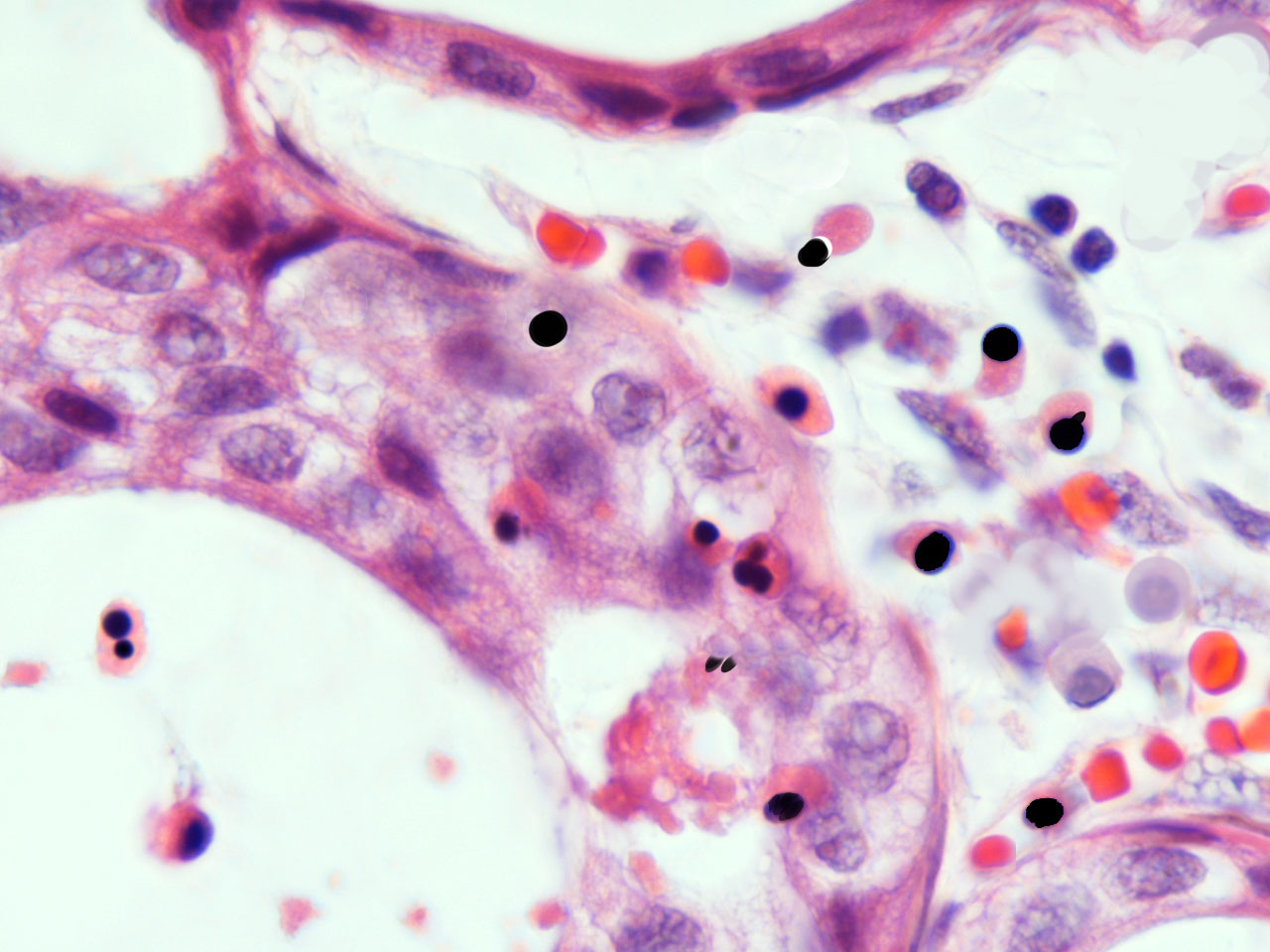

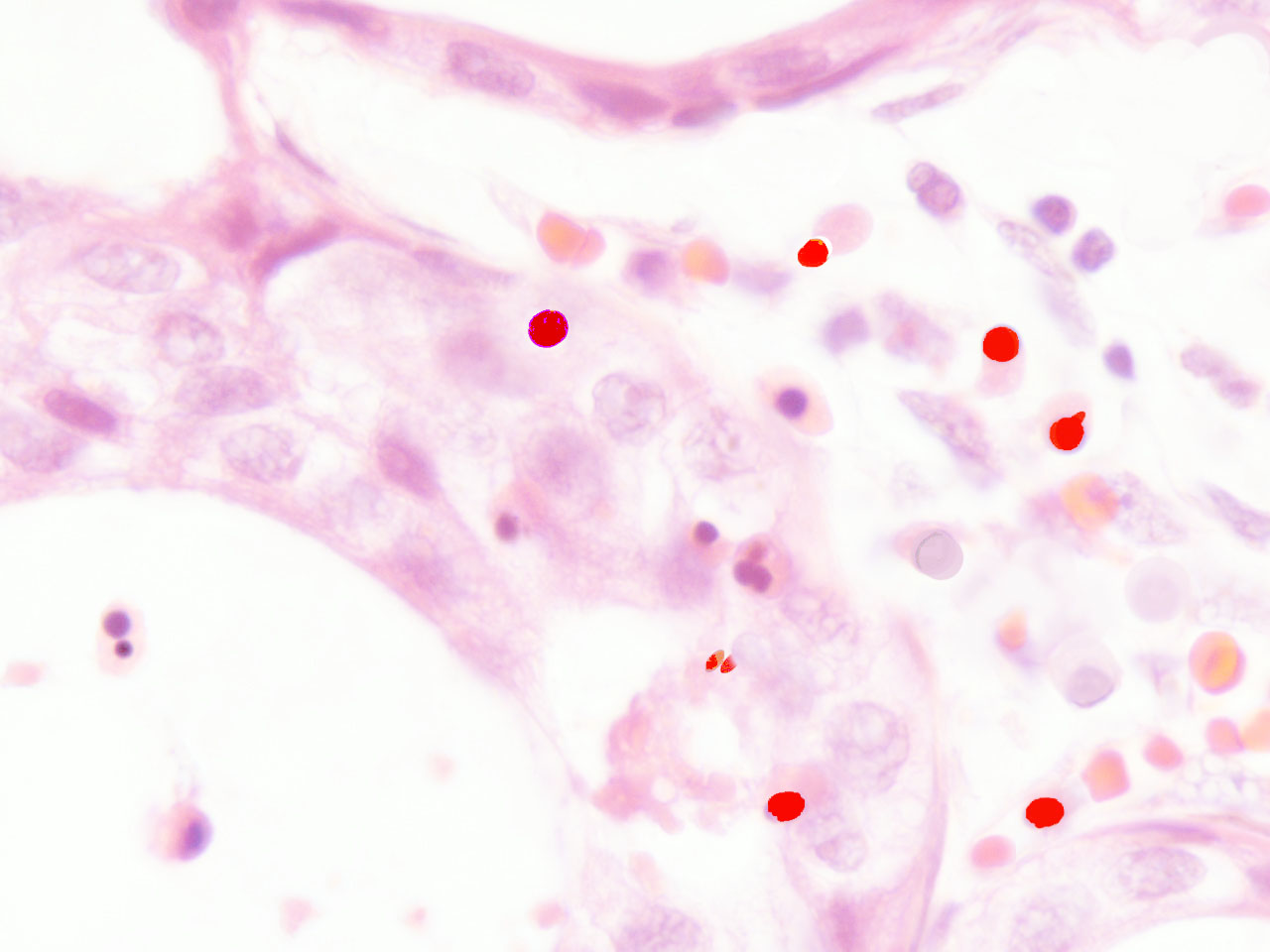

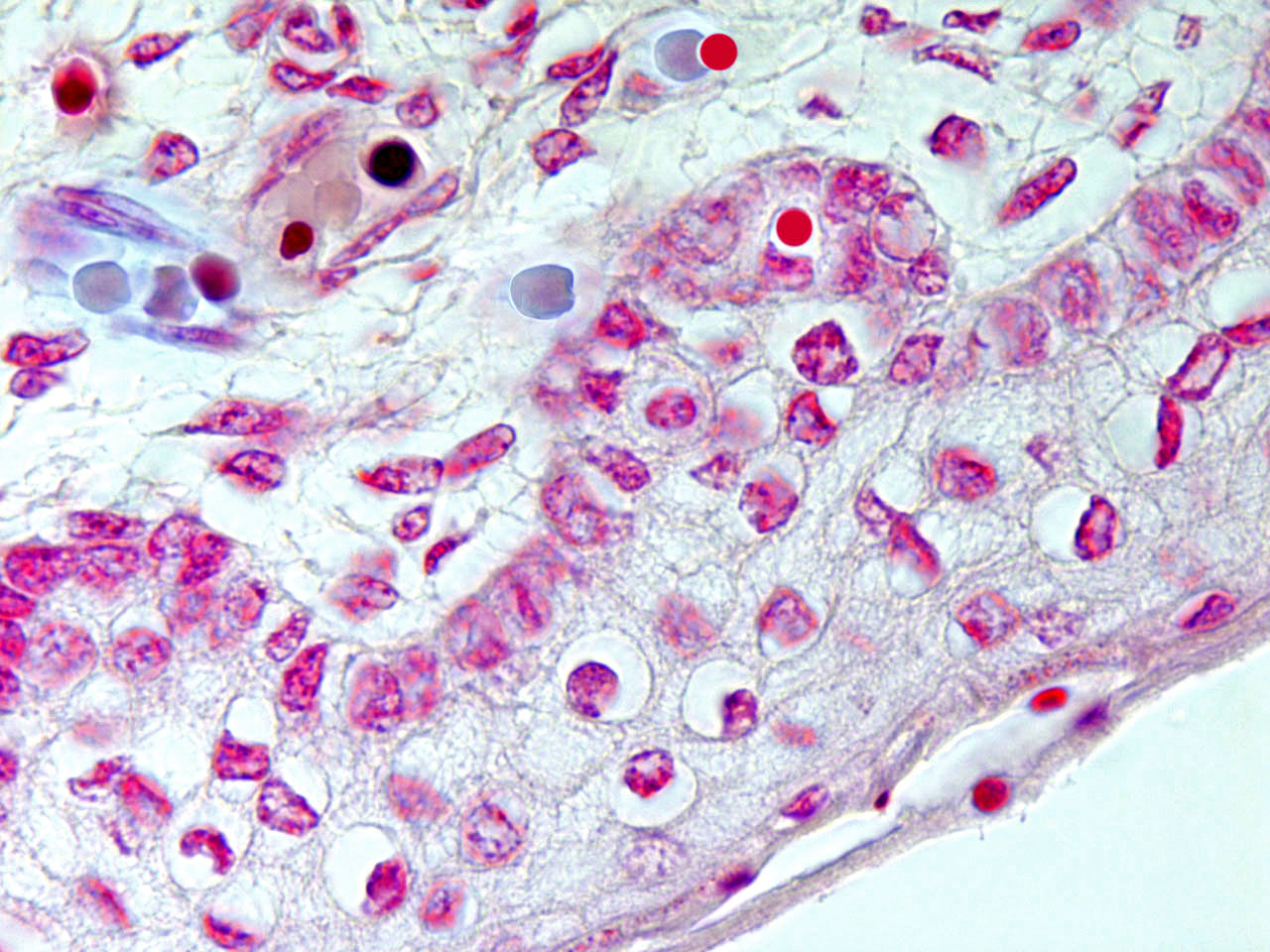

In malignant tumours, including both primary and metastatic tissues, a significant number of erythroblasts degenerate over neoplasic fields, with the freeing of acid fast, highly condensed hyperchromatic nuclei and micronuclei. At that time, resident neoplastic cells are not the only cells that undergo apoptosis; immigrant cells are also observed to undergo apoptosis-like phenomena (fig.3). In accordance with the AXS-model, these AF-lymphoid cells may supply nuclear mitotic potential to the target cells. One way to demonstrate the validity of this hypothesis is by neutralizing this deadly traffic, which relays bone marrow to the tumour, and measuring its effect on neoplastic behaviour.

fig.3 Human carcinoma. Erythroblasts enucleating near neoplastic cells. Apoptosis-like phenomena. Segmentation of nuclei with gamete like acid-fast nuclear fragments (centriole-DNA complexes).

SPECIFIC THERMOSENSITIVITY OF SPERM NUCLEI AND NANUS

The AXS-model links spermatogenesis and hemopoiesis through their common germ cell origin and their production of AF-DNA vectors. Effective gametopoiesis is only possible in the cooler environment of the human testis. We have linked this to the stabilizing effect of cooling on waxy membranes, assuring viable DNA vectors. AF-NANUS and spermatozoa are both waxy vectors of highly condensed chromatin. Polyunsaturated lipids impart short range thermolability to cellular membranes. Thus, only slight warming may be sufficient for the specific fluidification of these membranes. Membrane linked functions depend on close regulation of membrane fluidity. Ceramide present in waxy membranes also mediates contact between local electromagnetic field (EMF) and chromatin, and thermoregulation of nuclear “selfness” should be expected. Selfness imparts high instability to these nuclei, which are prone to spontaneous segmentation, and this is most likely prevented through extreme chromatin compaction. Cancerous fields in tissues are relatively acid, warm and hypoxic, and cells present in these fields appear disorganized, with marked loss of polarity. AF-NANUS entering these fields initiate apoptotic chromatin breakage, which probably reflects the disturbing local conditions and the sensitivity of these waxy nuclei . From this we can learn how to selectively eliminate these cells from peripheral blood.

RETRIEVING AND DESTROYING THERMOLABILE STEM CELLS FROM BLOOD AND BONE MARROW

Between bone marrow and tumours there is in general a bloodstream phase. Adult stem cells are difficult to obtain, since they are often present in very small numbers. However, transient periods of erythroblastemia often occur in cancer and may be detected in these patients. Furthermore, accounting for the specific thermosensitivity and fluidity of AF-enveloped NANUS, a selective cellular hemofiltration should be attempted. Subtle thermomodulation may be sufficient for destabilizing af-DNA vectors without damaging hematopoiesis. In procedures analogous to hemodialysis, connection to a warming device may trigger selective destruction of nuclei. Furthermore the nuclei of sperm and of other lymphoid cells have been called “karyogens” (16) reflecting the significant presence of metals in these nuclear chromatins. The latter observation means that metallonuclei and fragmented metallochromatin should be additionally purged by magnetoselection.

Consequences

The continuous retrieving of stem cells may be harmful, especially in younger individuals, in whom the contribution of stem cells to the soma is higher than in older patients. Lymphopenia, impeded development, inmunodefficiency, accelerated senescence and cachexia may be expected. After age 50, when most cancers arise, continuous and/or intermittent hemofiltration would be less iatrogenic.

CONCLUSIONS

The mutant phenotypes emerging in pre-neoplasic and tumour fields seem to trigger a bone marrow response, whereby there is a shift to a focal primary type of nucleated erythropoiesis.The mutant tissues attract AF-stem cells, disguised as immature AF-lymphocytes and as primary erythroblasts. The former probably attempt haplotype selection on the mutant target to obtain a tumour associated lymphocyte (3) response .On extrusion from erythroblasts, NANUS are expected to be null cells, with virgin nuclei open to all differentiating winds. These phenotypically evolving cells exhibit an essentially common distinguishing morphology, which is always present before they enter the differentiation pathway. That is, these naked nuclei (hematogones) can be tracked in formalin fixed and paraffin embedded tissues, since they simultaneously exhibit acid fastness (waxy membranes) and marked nuclear heterochromatin (chromatin compaction). Furthermore, acid-fastness in mycobacteria has been linked to the presence of mycolic acid in bacterial walls (18). The hypothetical presence of mycolates in AF-NANUS and sperm needs to be investigated. If mycolates are present, it may open the way for specific inmunophenotyping of these uncommitted AF-NANUS, vectors of transforming DNA (anti-mycolic acid antibody). Cancer appears to be a supracellular phenomenon dependent on two variables: the axial variable, as shown by the disposition of hematopoietic stem cells, which diminishes with ageing in a linear fashion; and the somatic variable, which increases with age. The latter, however, must be adjusted, since cellular mitotic senescence is not homogeneous and is subjected to asynchronous phenotype and clonal senescence (19). The concurrence of both lines coincides with the maximum risk of cancer. Mathematical models in cancer need to be rebuilt taken into account the forgotten central stem cell population. The axially based medullary stem cell pool presumably involved in neoplasia may explain, at least in part, the steady decline of acceleration in cancer incidence observed during the latter half of life (20). In most common cancers, which are sporadic, no mutations are expected to be present in the travelling hematogone. These af-nanus are chiefly vectors of mitotic potential. Genetic mutations are present in the target, atypical somatic cells. In the axs model, which is a two cell protagonist model, mutations can occur less frequently on the axial side (germ line) or in both the vector and the target. In the future treatment of solid cancers, it is important to preserve bone marrow hematopoiesis, thus avoiding any deleterious effects associated with the dangerous regenerative and rebound phenomena of immature erythroblastemia. The hypothesis of the proliferative dependence of tumours on exogenous stem cells of hemopoietic origin (1) opens new approaches and perspectives in the treatment of cancer. Cellular purging and “barrier” techniques should be investigated. To test this hypothesis, it has been proposed initially to apply an erythroblast NANU directed, continuous, thermo and magneto-hemofiltration and warming to patients with advanced metastatic disease, and monitoring the clinical evolution of the disease.

References

1. Houghton JM, Stoicov C, Nomura S et al. Gastric cancer originating from bone Marrow-derived cells. Science 2004; 306: 1568-71.

2.Palacios SL. The axio-somatic model in embryonic and tumoral development.Med Hypotheses 1994; 43: 86-92.

3.Palacios SL. Histogenesis of malignant melanoma of the skin: the role of lymphocytes in the transformation of tissue development units. Med Hypotheses 1989; 30: 231-40.

4. Gurdon JB, Laskey RA, De Robertis EM, Partington GA. Reprogramming of transplanted nuclei in amphibia. Int Rev Cytol Suppl 1979; (9): 161-78.

5. Sapp J. Freewheeling centrioles. Hist Philos Life Sci 1998; 20: 255-90.

6. Palermo G, Munne S, Cohen J. The human zygote inherits its mitotic potential from the male gamete. Hum Reprod 1994; 9: 1220-5.

7. McFarland W. Microspikes on the lymphocyte uropod. Science 1969; 163:818-20.

8. Berg JW. An acid-fast lipid from spermatozoa. AMA Arch Pathol 1954; 57: 115- 20.

9.Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

10. Callan HG, Taylor JH. A radioautographic study of the time course of male meiosis in the newt Triturus vulgaris. J Cell Sci 1968; 3: 615-26.

11. Kuehn BM. Goodbye, Dolly; first cloned sheep dies at six years old.J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003; 222:1060-1, 1065

12. Palacios-Llopis SL. Evidence for the erythroblastic origin of hematogones in humans. Pathology International 2004; 54 (Suppl 2): A38 (abstract).

13.W St C Symmers Systemic Pathology. Blood and Bone Marrow ed. By SN Wickramasinghe.1986.p78.

14. Davis RE, Longacre TA, Cornbleet PJ. Hematogones in the bone marrow of adults. Immunophenotypic features, clinical settings, and differential diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol 1994; 102: 202-11.

15. Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001; 414:105-111.

16. Guieysse-Pellissier A. Caryanabiose et gréffe nucleaire. Arch.d.´Anatomie Microscopique 1912;13:1-94.

17.Dorland´s Medical Dictionnary. Karyogen. 26th edition. WB Saunders Company.1984.

18. Ellis RC, Zabrowarny LA. Safer staining method for acid fast bacilli. J Clin Pathol 1993; 46: 559-60.

19.Palacios Llopis S. Is a bi-clonal interaction, analogous tothat underlying embryogenesis, the origin of the earliest malignant phenotype? Med Hypotheses 1984; 13: 175-88.

20. Frank SA. Age-specific acceleration of cancer. Curr Biol 2004; 14:242-6.

Human carcinoma. Erythroblasts enucleating near neoplastic cells. Apoptosis-like phenomena. Near naked nuclei (Nanus) of compact chromatin. Segmentation of nuclei with gamete like acid-fast nuclear fragments (centriole-DNA complexes)

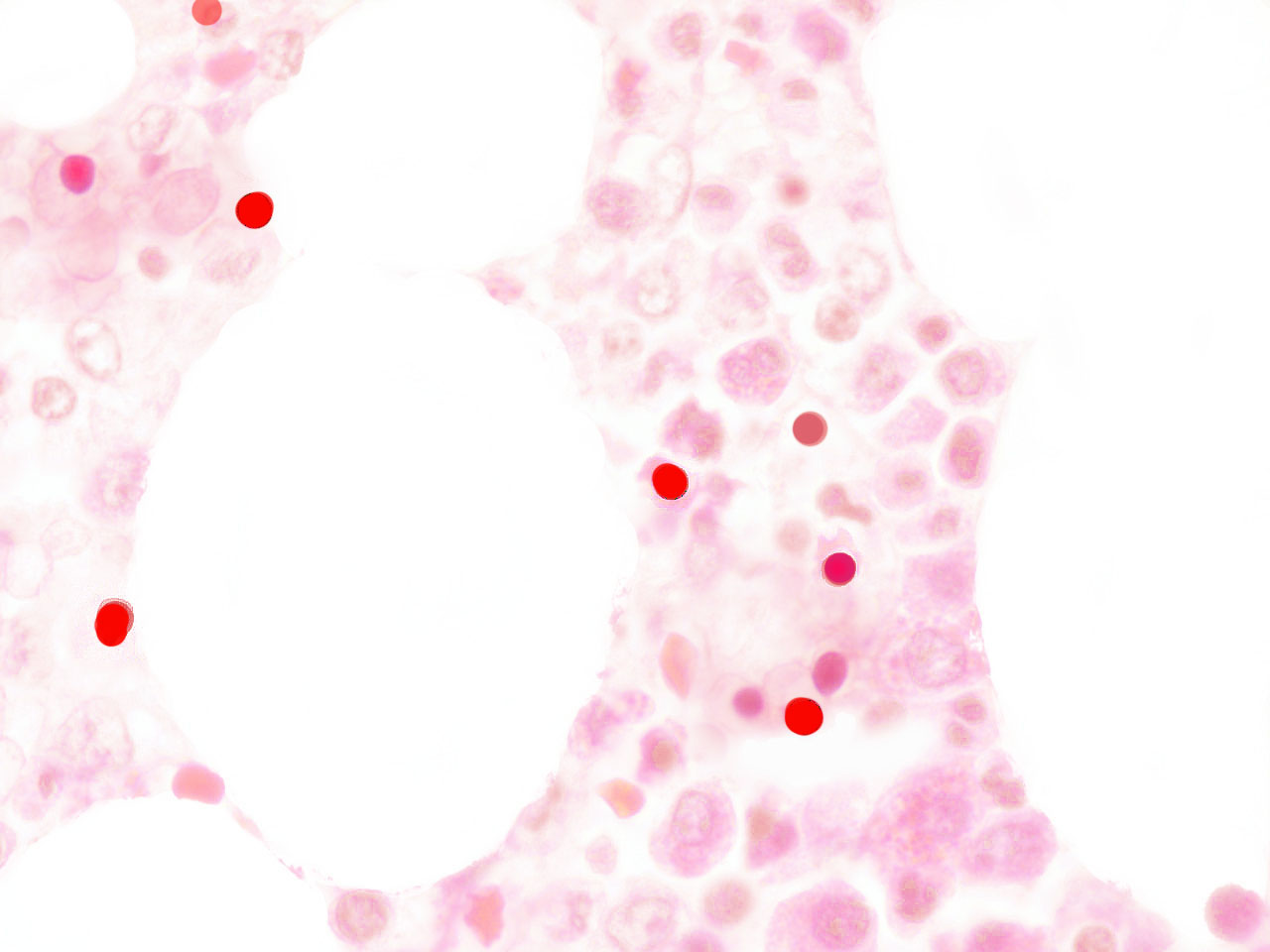

Acid-fast spermatogenesis in the testes. The origin of acid-fast DNA vectors.

Human carcinoma. Erythroblasts enucleating near neoplastic cells. Apoptosis-like phenomena. Segmentation of AF-nuclei with gamete like acid-fast nuclear fragments (centriole-DNA complexes)

Skin development in humans. Contribution of enucleating AF-erythroid cells to epidermal niches in the foetus.